A couple of months ago I was lucky enough to relocate to beautiful Waiheke Island. Upon moving here, I learned that all Waiheke homes are supplied water through individual rainwater tanks. My only prior experience with relying on a water tank was when I lived on a lifestyle block in the Wairarapa as a child for a few years, and my only memories of that tank was how awesome it was to climb on and jump off of (sorry, mum). Now, as a renting adult who doesn’t want to go thirsty and shell out the $300+ if our tank runs out, I am much more mindful of water use. My new focus on water conservation has led me to think about accessibility of clean water across Aotearoa, as well as globally, which I realised I’ve taken for granted. I decided to do some investigating.

The Aotearoa context

Is water as plentiful and safe in Aotearoa as I previously assumed? According to the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), water is “relatively abundant” in NZ due to the climate and topography, with a number of good quality water sources, including snowfields, rivers, and lakes. However, climate change is expected to impact our freshwater access. According to the Ministry for the Environment’s 2020 freshwater report (MfE), the changing climate will affect “when, where, and how much rainfall, snowfall, and drought occur”, which will in turn impact the amount of water in our lakes, rivers, glaciers, and soil. Droughts are expected to become more frequent, particularly in regions that are already prone, such as Eastern Canterbury and Gisborne, and this will impact access to drinking water in communities who are dependent on rain water.

On top of potential freshwater accessibility issues, water pollution has become an increasing concern in Aotearoa in recent years, due to rural and industrial land use, as well as urban development. MfE’s freshwater report states that nutrient, chemical, and sediment run off from various industries and projects means that almost all of our rivers (95-99%) and many of our lakes (67-77%) are polluted to some degree. So, while we’re fortunate to have relatively plentiful water supplies in NZ, climate change and human activity are putting our freshwater ecosystems under a lot of stress, and pollution is a pervasive issue.

The global context

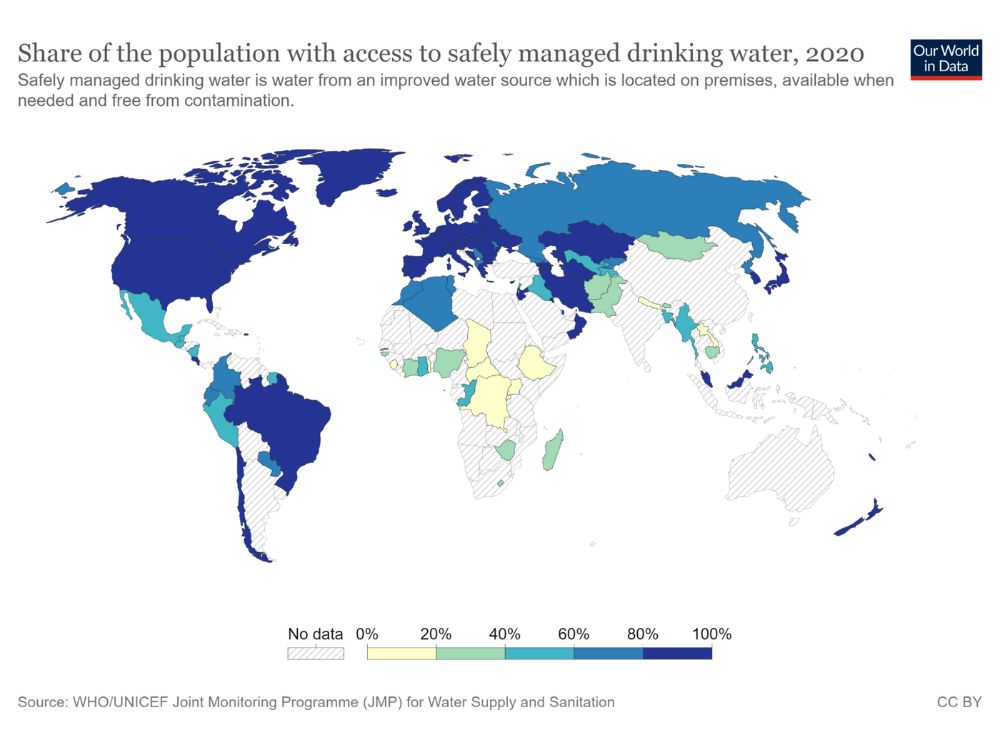

What’s happening with water on a global scale? According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), we are in a global water crisis, with over two billion people living in water-stressed countries and another two billion people using drinking water sources contaminated with faeces. Contaminated water causes diseases such as diarrhoea, cholera, dysentery, and typhoid, with diarrhoea alone caused by unsafe water is estimated to kill over 800,000 people every year. While WHO states that access to safe water is increasing (1.8 billion people have gained access to basic drinking water services since 2000), it also acknowledges that water scarcity is expected to worsen in some regions as a result of climate change and population growth. As in Aotearoa, drought is expected to continue to worsen in areas of the world that are already prone, and water accessibility is also expected to be impact by rising sea levels, which are salinating freshwater sources.

Water we going to do?

The above data paints an alarming picture of global freshwater access, now and in the future. So what are we doing about it? The Economist posits that the water sector has suffered from a lack of attention and innovation in the past, however this is beginning to change. Governments are investing more money into water resilience, such as the $700 million fund the NZ government implemented in 2020 to support new clean water standards. Companies providing water scarcity solutions are also experiencing structural growth of 5-10% a year due to demand.

Technology is being developed to improve efficiency of desalination plants, wastewater treatment plants, and smart sensors that alert to leaks. However, according to Edeltraud Guenther, co-editor of Unconventional Water Resources (2022), “It is a human approach to think that sufficient technology will tackle the problem. But if there’s no rain, if the groundwater level gets lower and lower, if we cannot drill deeper, and there is no option for desalination, this is when we start thinking, but by then it’s very often too late.” Alongside strong governance, investment, and technological development, there needs to be global collaboration and a reduction in water demand.

In Aotearoa, the government has developed its Government Freshwater Work Programme, which aims to provide regional councils with direction on how they should manage freshwater, speed up council planning processes, protect wetlands and streams, and improve farming practices. At an individual level, we can contribute to the freshwater cause by reducing our water use and by avoiding contaminating waterways.

Our tips

Reducing water use:

- Cut down your shower time. According to Waterforlife, showers account for 27% of water use in the home overall, so cutting down your shower time can significantly reduce your water consumption, as well as save you money.

- Only run your dishwasher and washing machine when you have a full load, and change them to water-efficient settings, if available. In the same vein, only wash dishes and clothes if they are actually dirty. If you need to replace your machines, look for water and energy efficient option

- Check your home for leaks by inspecting all taps and look for damp spots in your property.

- Turn your taps off when using your sink, such as when you’re brushing your teeth or peeling vegetables.

- If you have an InSinkErator, ditch it in favour of composting your food scraps. Not only do InSinkErators use water, but their contents end up in landfill.

- Purchase second hand clothes; the fashion industry use massive volumes of water to grow natural fibres and dye fabrics.

- Reduce your consumption of meat and dairy products – similar to the fashion industry, huge volumes of water are required to farm these.

Avoiding contamination:

- Pick up litter so that it doesn’t end up in a waterway or block a drain.

- Be mindful when gardening – if fertiliser gets onto paved areas, sweep it back in to your garden, and compost or leave organic matter in your yard, so it doesn’t clog storm drains.

- Wash your car or other items where water can flow into gravel or grass area, not into the street.

- Shop for non-toxic and biodegradable cleaning products.

- Only wear reef and river safe sunblocks and creams into waterways. Look for HEL’s Protect Land + Sea Certification Seal on products, to certify that they do no contain environmental pollutants.

Future thinking: imagine if all houses had the ability to recirculate used water to wash clothes, dishes, and bodies?

Written by Kate Lodge, Sustainability Consultant at Go Well Consulting

https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/27088/direct

https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Files/our-freshwater-2020-summary.pdf

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drinking-water

https://www.concernusa.org/story/global-water-crisis-causes/

https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/cleaning-our-rivers-and-lakes

https://www.concernusa.org/story/global-water-crisis-causes

https://www.waterforlife.org.nz/water-saving-tips