About Recycling

DEFINING RECYCLING, ITS CHALLENGES, WHAT IT LOOKS LIKE IN PRACTICE

& HOW TO IMPROVE RECYCLING RATES

Although recycling has a role to play in achieving a circular economy, and vast amounts of energy and resources can be saved through recycling, it is not the answer to our problems.

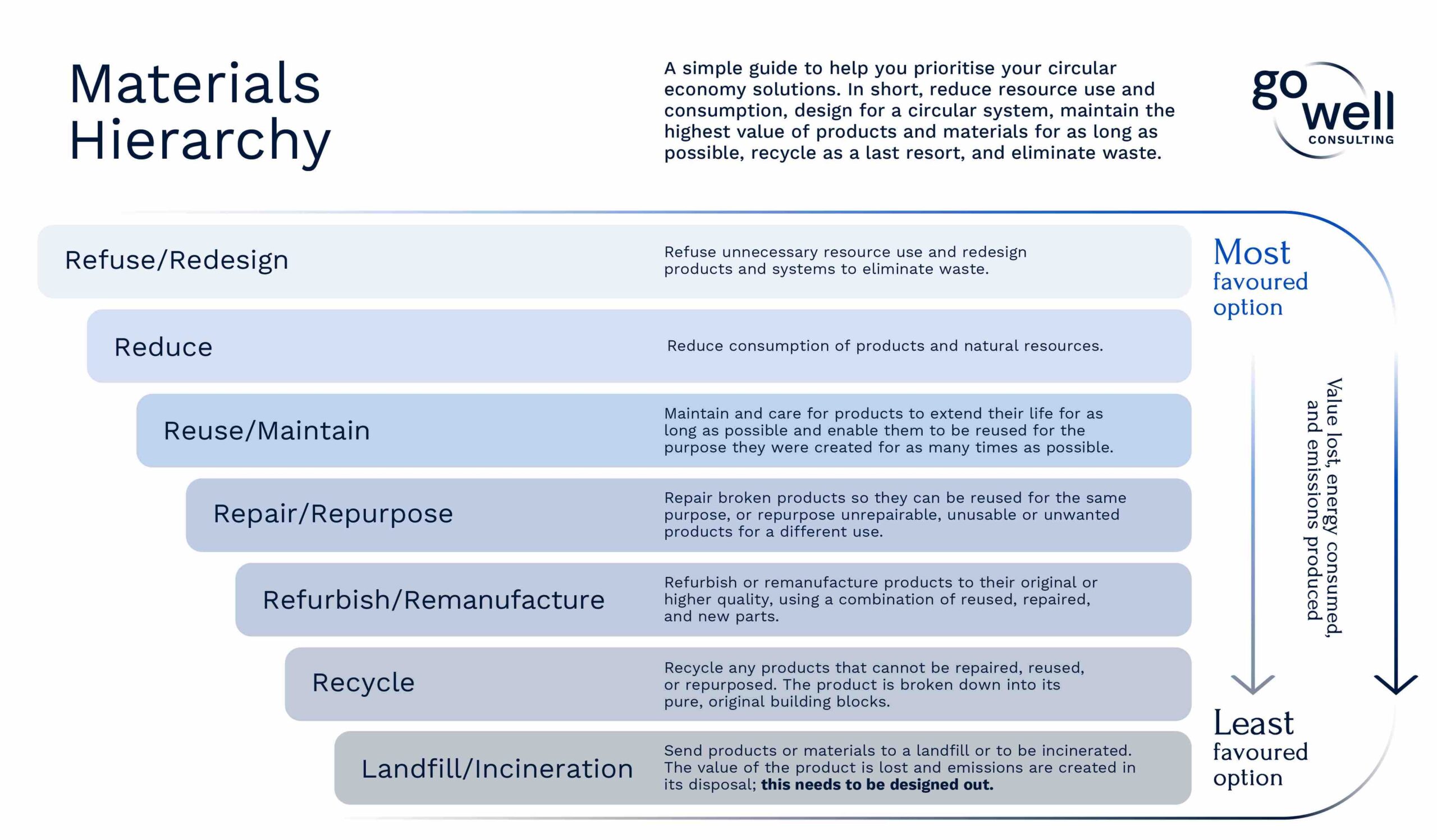

We are, after all, in the mess we are despite recycling being a part of our economic systems for decades. We cannot address recycling, without first acknowledging that it is the last viable option in the Materials Hierarchy and that businesses should be striving to redesign, reduce, reuse, repair, refurbish or manufacture before resorting to recycling.

For businesses, product design and packaging options are key to moving up the Materials Hierarchy (see diagram below). When thinking about design and packaging, businesses most consider the quality and longevity of their product materials, as well as whether packaging is required at all.

Could your product be provided ‘naked’? Is your product repairable? Can you take your product back to be refurbished or remanufactured? Could your product be designed with more durable materials, or materials that are recyclable, rather than downcyclable (continue reading for clarification between the two)? Could your product be provided in a refillable container? Could your product be leased, rather than sold?

Thinking outside the box is critical for businesses seeking to become circular and to remain competitive – get in touch if you’d like some support with this.

Go Well Materials Hierachy

Maintain the highest value of materials for as long as possible, reduce resource use and emissions, and eliminate waste.

What is Recycling?

Recycling is the process of taking a product or material back into it’s original pure building blocks (e.g. an aluminium can back into an aluminium sheet), or a new material (e.g. Tetra Pak into SaveBOARD), which can in turn go through that same process again. This process most commonly involves heat and pressure to break, melt, and press the materials into their recycled form (known as ‘mechanical recycling’), although we note that chemical recycling is increasing in its scale and capability. Recycling is the process for inorganic material, composting is the process for organic material.

Collection & Sorting

In order for a product or material to be recycled, it requires the critical steps of collection and sorting. Typically, materials are collected through kerbside recycling programmes or recycling drop off centres, then sorted at a Materials Recovery Centre (MRF). At the MRF, non-recyclable or contaminated items are removed by hand, and the remaining material is either sorted by hand or by automated machinery (or both). The separated materials are then bailed together and sold on commodities markets to manufacturers to create new products.

Recycling vs Downcycling

It is important to understand the difference between recycling and downcycling. Not all materials can be recycled and maintain the same level of structural quality. Plastic and paper are only able to be recycled a certain number of times before their quality decreases to the point where they can no longer be used. When a material or product is recycled into a lower grade product, is it know as ‘downcycling’. Despite being made of ‘recyclable’ materials, downcycled items will either end up in landfills, incinerated, or end up in our environment.

Recycling, on the other hand, is a closed-loop system, where the materials maintain their structural quality, integrity, and value. For example, a glass bottle being turned into another glass bottle is recycling, whereas a glass bottle being processed into roading or building materials (that will ultimately end up in landfill), is downcycling.

Recycling Different Materials

The recycling method of each material varies depending on the material in question; we have provided an overview of the most common recycling process for major materials below.

Plastic

There are a number of different types of plastics, some of which cannot be recycled, so the first step of the recycling process is sorting the plastics by type. The numbers you see on plastic packaging (1-7) are resin numbers that reference what type of plastic they are. Once the plastics are sorted, they are washed, shredded, melted, pelletised, and generally sold on to be moulded into new products. Plastics contain polymers (long chains of molecules), which shorten each time they are recycled, and they can also become cross-contaminated in the recycling process, which leads to the material degrading over time. There is some debate about how many times a piece of plastic can be recycled, but it’s estimated at somewhere between 1-10 times before it can no longer be used and ends up in landfill, in the open environment, or incinerated. Check out recycle.co.nz for more details on the different plastic types.

Paper/Cardboard

Similar to plastics, paper and cardboard need to be separated into different types and grades after collection. The grade of the paper and cardboard is determined by the length of the fibres, which – again, similar to plastic – shorten every time an item is recycled. Once sorted, paper and cardboard are shredded at a mill, after which they are mixed in with water and chemicals and heated to separate the fibres. Fibres are passed through a screen to remove any ink, adhesives (e.g. cellotape), or other contaminants, and then sprayed on to a mesh conveyor belt, where water drips through and the fibres start to bond together into a sheet. The sheet is pressed, heated, and rolled into the correct thickness. Paper and cardboard can be recycled an estimated five to seven times before the fibres become too short to recycle again.

Glass

After collection, glass is broken into small pieces (cullet) and machine sorted into different colours, then washed to remove any contaminants. Next, the glass is crushed and mixed with raw materials like sand or ash to colour or enhance the material as needed. Lastly, the glass is melted in a furnace and then moulded or blown into new products. Unlike plastic and paper/cardboard, glass is not degraded through the recycling process, and can be recycled infinitely. However, this process is only for glass bottles and jars; other glass items, like drinking glasses and mirrors, cannot be recycled with glass bottles, because they melt at a different temperature.

Steel & Aluminium

Food and beverage cans are typically made from steel and aluminium, which require different recycling processes. Aluminium cans are first shredded and then mechanically and chemically cleaned to remove any coating. Steel cans need to be submerged into a chemical solution to dissolve their tin layer, before being drained and rinsed. Both aluminium and steel go on to be melted in a furnace, before being poured into casts. Like glass, metals are not degraded through the recycling process, and can be recycled an infinite number of times.

The Challenges of Recycling

Recycling is always a better alternative than sending materials to landfill, incineration, or littering, and it has a lot of benefits: it conserves energy and resources, reduces emissions, cuts down the amount of materials in landfill sites, and creates jobs. However, there are many obstacles to recycling and unavoidable issues with the process itself.

Human Error

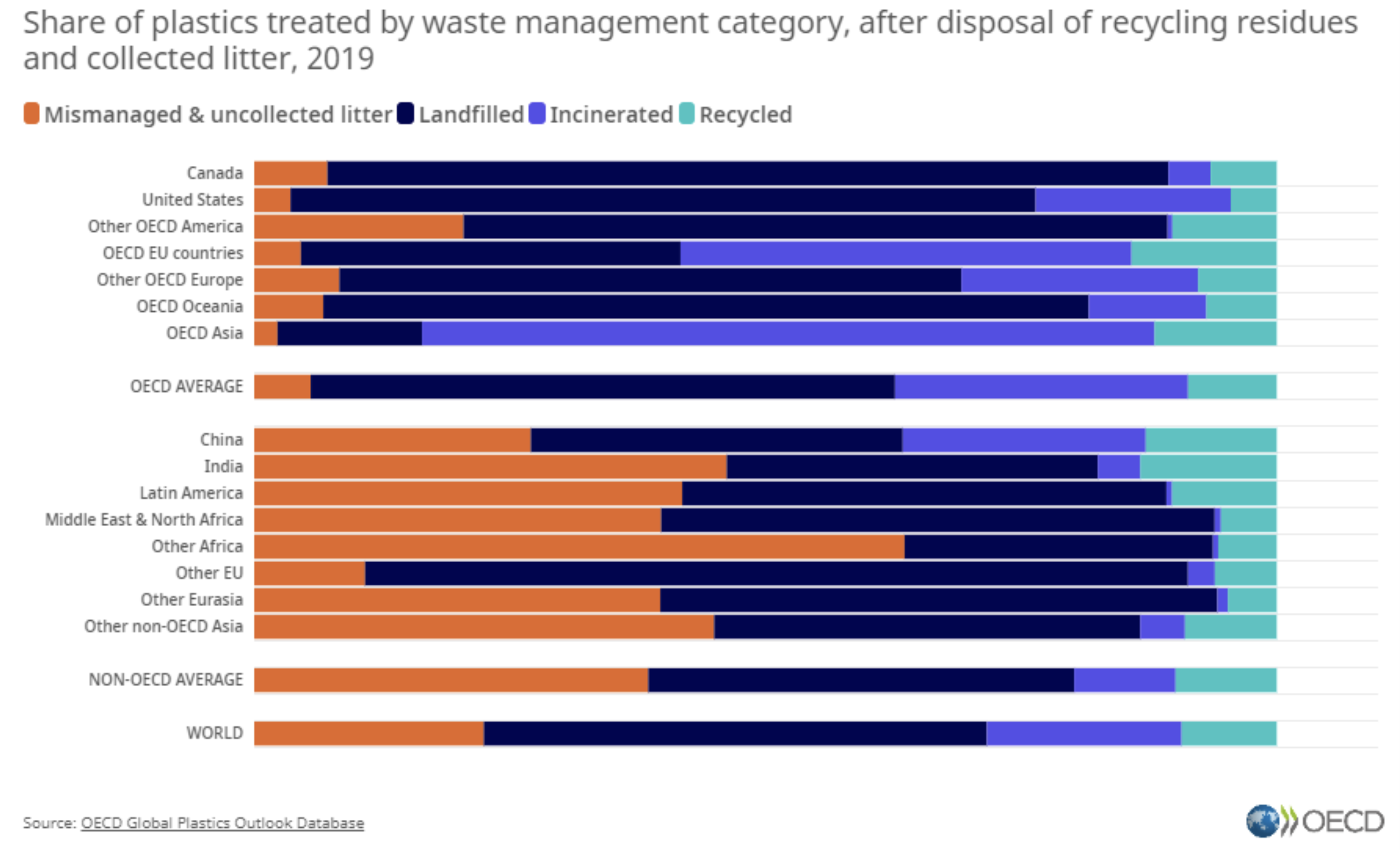

Just because an item is recyclable does not mean that it will be recycled. According to the OECD, only 9% of plastics produced globally have been recycled. People often dispose of their recycling incorrectly because they either don’t know whether an item is recyclable or they don’t know where it should go. There is no standardisation of recycling streams globally, or nationally within most countries, and the types of items accepted in different collections varies widely from place to place, which means there is a lot of public confusion about how to recycle correctly. Inconsistency and confusion breeds scepticism, and there is a strong public narrative that all recycling ends up in a landfill, regardless of where you put it.

Energy & Emissions

While recycling can reduce the environmental impact associated with producing virgin materials, it still requires its own energy and creates its own emissions through collection, transportation, and the recycling process itself.

Cost & market variability

Recycling is an expensive process, and is only cost effective if there are markets to purchase the recycled products. Because the cost of virgin materials is so low, recycling can often face weak and variable markets. National recycling schemes, such as the the New Zealand soft plastics or batteries ones, are known to stop without warning when markets dry up. High costs and inconsistent markets mean businesses are often reluctant to invest money into recycling infrastructure.

Lack of infrastructure

All material and products are technically recyclable, but without appropriate and accessible infrastructure they cannot be recycled at scale or cost effectively. We lack the infrastructure to recycle many materials in New Zealand, including most types of plastic and metals. For many countries, it is not financially feasible to develop the infrastructure needed to recycle all the materials they produce, which means they either end up in landfill, or get shipped overseas, which creates more emissions, and often ends up in developing countries with little or no environmental legislation and enforcement.

New Zealand's Recycling Standardisation

On 1st February 2024, New Zealand’s new recycling standards came into effect, which means New Zealanders are now following the same guidelines for which items can and can’t go into their kerbside recycling bins. Previously, the items accepted in kerbside recycling were determined by local councils (who are responsible for sorting what they collect and finding recyclers to buy all the different materials). This new standardisation has been based on what materials are valuable to recyclers and therefore are highly likely to actually be recycled: glass bottles and jars, paper and cardboard, aluminium and steel tins and cans, and plastics 1, 2, & 5. You can read more about the recycling standardisation in our blog post here.

Below is a short video that gives an overview of the recycling standardisation.

Recycling Resources

Below are some informational videos about how recycling works in two of New Zealand’s major cities, which will be similar to major cities around the world. Typically, big cities use machinery to sort their recycling, while smaller areas often rely on manual sorting. The videos also outline the risks of recycling incorrectly. It must be stressed that kerbside recycling varies from region to region, and it’s critical that you check your local council website to understand what items are accepted for recycling in your area, and where it goes.

Recycling in Practice

Availability of recycling options and infrastructure varies widely across the globe. As mentioned above, there is no international standardisation of recycling streams and what can be accepted in each one, which creates public confusion about how to recycle correctly. There is often not even recycling standardisation at a national level, with different cities and communities within the same country accepting different items for recycling, which further increases confusion; in New Zealand, for instance, Tetra Pak (liquid paperboard packaging) cartons are collected for recycling in the Auckland region, but nowhere else, due to the location and capacity of the recycling plant. This public confusion, paired with a lack of recycling options and infrastructure, has led to poor recycling rates globally; it’s estimated that only 19% of the world’s waste is recycled (or composted) each year, and only 9% of plastics ever created.

How to Improve Recycling Rates

National and local governments have an important role to play in improving recycling rates, through investment in infrastructure and local initiatives, the development of comprehensive kerbside recycling collections, regulation of businesses and the products they put on the market, and public education and engagement.

Businesses who sell products can improve recycling rates through effective packaging design and clear communication of end-of-life options. Businesses can make their packaging more easy to recycle by:

- Using a single material, where possible;

- If multiple materials must be used, ensuring they are easily separable;

- Avoiding toxins and additives in materials;

- Using recycled materials (this helps to create further demand for recycled materials, thereby improving the economic viability of recycling);

- Clearly labelling packaging, specifying the material composition of the product and its end-of-life options.

Choosing the right material for your product packaging can be a challenging undertaking. Consideration needs to be given to the durability and safety of the material in protecting your product, as well as the environmental impact of sourcing the material and its recyclability. Before making any decisions, businesses need to know what the recycling options are for different materials in the areas they sell products in. New Zealand Trade & Enterprise (NZTE) has an excellent guide on redesigning packaging to be more sustainable, which provides the pros and cons of common materials, and is applicable to businesses outside of New Zealand.

Although improving recycling rates is important, it should be stressed again that recycling is not a silver bullet for our sustainability challenges and goals. Government, businesses, and community members should all be striving for waste prevention, rather than waste management, to move us towards a circular, regenerative economy.

Learn more about our world with our useful resources.