About Composting

DEFINING THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF COMPOSTING, THE BENEFITS & CHALLENGES

& HOW TO IMPROVE COMPOSTING RATES

Composting is a vital component of transforming our economy into one that is circular, regenerative, and inclusive. When we compost food and other organic matter, we are working in harmony with the laws of the natural world and the circle of life by returning important nutrients back into the soil.

This results in healthy soil, which promotes healthy plant growth, and ensures stability (reduces erosion). Composting is also a critical means of keeping organic matter out of landfill; when organic matter ends up in a landfill, it decomposes anaerobically (without oxygen) and produces methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. It has been estimated that if food waste was a country, it would be the third largest producer of carbon emissions behind China and the United States. In New Zealand, despite the fact we have modern-day landfills that capture much of the methane and burn it to create electricity, 4% of our total greenhouse gas emissions are from food and organic matter in landfills.

Composting is critical for dealing with discarded food and organic matter and plays a vital role in a circular economy, but we want to highlight that – just like recycling – composting is not the first or only solution. Globally an estimated one-third of all the food we produce is lost or wasted between farm and fork each year – that’s 1.3 billion tonnes of food that is never eaten. The more food that is not eaten, the more food we need to produce, and the more land, water, and energy we consume. 26% of global greenhouse emissions come from food.

Research into the amount of food thrown away in Aotearoa by Love Food Hate Waste found that New Zealand homes throw away 157,398 tonnes of food per year, all of which could have been eaten. This equates to 86kgs or $644 of edible food per household, enough food to feed the whole of Dunedin for just under three years!

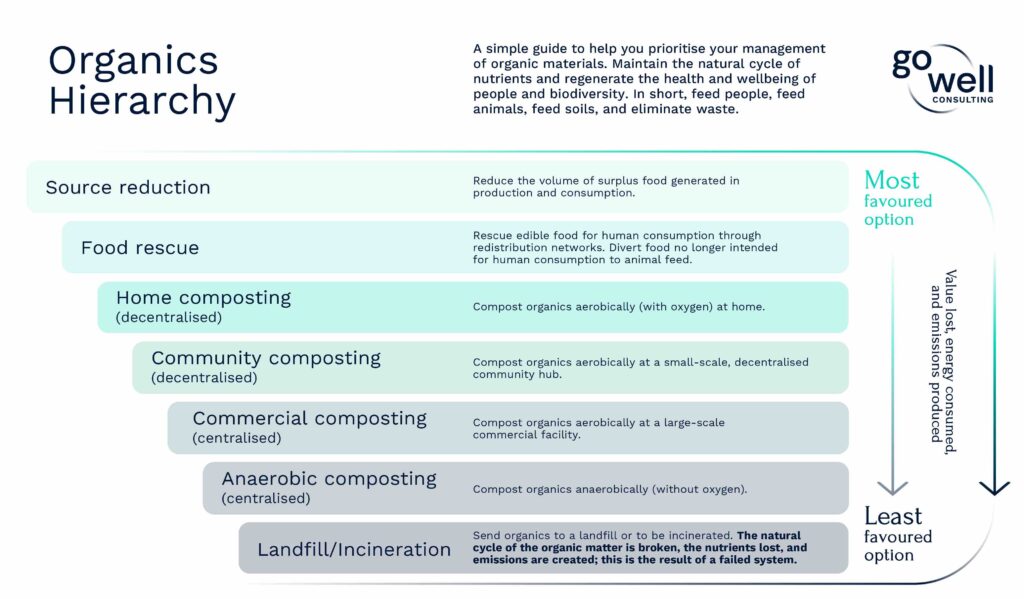

So the point must be understood that even if we were to compost all food we threw out, our food production and consumption patterns would still not be sustainable. We must focus on systems design and the elimination of waste above everything, as per the Organics Hierarchy below.

What is Composting?

Composting is the controlled, natural process of organic decomposition into a nutrient-rich material (compost). In the composting process, organic matter is broken down by organisms, such as worms, bacteria, and fungi. The end result is compost, which looks like (and smells like) soil and is a natural fertiliser. Composting can be done aerobically (with oxygen) or anaerobically (without) and in a residential, community, or commercial setting.

Home Composting

There are different ways to compost at home: in your backyard with a pile or bin that you tend yourself, or vermicomposting (worm composting) with a bin. Note – bokashi systems are another option, great for apartment living, but the contents must still be composted, buried, or fed to worms (but be mindful of what you give them, they can be fussy!). Home composting is the most preferred composting option on the Organics Hierarchy because it means there is no requirement for transportation of the organic matter, which is likely to require energy and/or produce emissions.

Community Composting

Community composting is any local, small-scale program that collects organic matter for composting from the community, using either a drop-off or collection system, or both. An example of this is Kaicycle in Wellington or Kelmarna in Auckland, urban farms that collect discarded food from people and businesses, or ShareWaste, an online platform that connects people in New Zealand needing to dispose of unwanted food with people that have the ability to compost it. Community composting is the same process as backyard composting, just on a slightly larger scale, designed for multiple users within the community, not just a single household. These community facilities often also have the scale and capability to achieve hot compost conditions that result in a far faster process and can kill unwanted weeds, seeds, and pathogens.

Commercial Composting

Also known as ‘industrial composting’, commercial composting is designed to process large volumes of organic matter. The compost produced by commercial composters is often sold to farms and nurseries. Commercial composting uses the same biological processes as home composting, however, there are a few different methods, and facilities can also use technology to turn a broader range of organic materials into compost. Compostable food packaging, for example, often requires high temperatures to break down that can usually only be reached by commercial methods (or efficient and well-managed community composting). Commercial composting is lower on the Organics Hierarchy than home and community composting because of the energy use and emissions associated with collecting and transporting the organic matter to the facility, as well as running the facility itself. Another big issue is contamination: similar to recycling facilities, commercial composting facilities often receive contaminants in their collections (nonbiodegradable matter). Separating items can be extremely messy and challenging, but if contaminants aren’t removed then it negatively impacts the quality of the compost produced, and in turn the soil it is applied to. This can often lead to facilities imposing strict guidelines around what they will and won’t accept, such as not accepting any compostable packaging.

Anaerobic Composting (AKA Anaerobic Digestion)

Anaerobic composting, also commonly known as anaerobic digestion, is composting without oxygen. It is the least preferred method of composting because its main byproduct is methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. In contrast, aerobic composting produces no methane and only a small amount of carbon dioxide (1/20th as harmful as methane), which is part of the natural carbon cycle anyway (compared to burning fossil fuels which imports new carbon into the atmosphere). Anaerobic composting also produces less heat than aerobic composting, which can result in the survival of some pathogens, weeds, and seeds. Anaerobic composting should be our last resort when considering composting options. It is however often more favourable for composting contaminated organic matter or biodegradable sewage sludge.

The Benefits of Composting

Composting yields benefits for the planet, businesses, and communities:

Environmental benefits

- Reduced material to landfill and, consequently, reduced emissions.

- Improved health of soil and reduced soil erosion, leading to healthier and more plentiful crops.

- Conservation of water, due to composts’ ability to help soil retain and transfer water. This also makes compost and healthy soil an effective tool for stormwater management.

- Replacement for chemical fertilisers, reducing pollution.

Business benefits

- Reduced or eliminated costs associated with sending materials to landfill.

- Revenue from selling compost. Note – you need certification and clearance to sell compost.

- Possible increased profits from higher crop yields

- Decreased costs from reduction in chemical fertilisers.

- Improved awareness of what’s being thrown out, which can be the first step in curbing unnecessary spending.

Community benefits

- Home and community composting builds sustainability awareness, education, and engagement.

- Community composting encourages social inclusion, empowerment, and support.

- Community and commercial composting provides local jobs and volunteering opportunities.

- Composting provides communities with healthier food and more resilient food systems.

The Challenges of Composting

Composting can yield a wide range of benefits but faces challenges at the household, community, and commercial levels:

- Contamination: as outlined earlier, contamination is a significant problem for commercial composters, as well as community and household composters. Contamination occurs whenever any non-organic material, such as food stickers or plastic cutlery, is mixed in with organic waste. It is costly, timely, and sometimes dangerous to remove, therefore if a collection is heavily contaminated it is likely to be landfilled. Contamination is very common, due in large part to a lack of public understanding about what can and can’t be composted, which is exacerbated by the wide range of ‘compostable’ and ‘biodegradable’ packaging on the market, which all require different conditions for breaking down and often aren’t home compostable or accepted in community or commercial facilities.

- Emissions: commercial composting facilities rely on trucks to collect and transport organic material, as well as machinery to operate their facilities, which means fuel consumption and related emissions. Until new technology is developed, fuel consumption remains a disadvantage of large-scale composting.

- Space and cost: whether it is done at a household or commercial level, composting requires a set space and money to operate. Many people don’t have gardens in which to set up a composting site, or cannot afford the cost of purchasing infrastructure, like bins and worms. Likewise, towns and cities often struggle to find and afford space to develop and run community composting sites and facilities.

- Smell: decomposing organic waste can smell – bad – and this can be a deterrent for both people setting up their own compost, as well as those in the vicinity of a community or commercial compost facility. The smell also attracts rodents and other pests, which can be timely and expensive to deal with. It is important to note that a bad-smelling compost is a bad-performing compost. It is a sign that your compost is or is becoming, anaerobic and it needs more oxygen and/or dry material.

Composting packaging

Compostable packaging has risen in popularity and prevalence in recent years, with many seeing it as a viable solution to our plastic packaging issues. Yet compostable packaging comes with many of its own problems: the varied and confusing types and terminology, the fact that many commercial composters will not accept them as they do not add any nutritional value to compost, and the methane produced if they are disposed of into landfills. For more on compostable packaging, we recommend the below resources:

How to Improve Composting Rates

National and local governments have an important role to play in improving composting rates, through investment in infrastructure and local initiatives, the development of kerbside compost collections and supportive consenting laws, regulation of businesses producing and selling food and/or compostable packaging, and public education and engagement.

All businesses, regardless of whether they produce or serve food, should at thievery least ensure they have a compost collection in place at their premises (or compost on site), and that their staff are educated on how to use it.

Individuals interested in composting at home can find useful information on The Compost Collective. LoveFoodHateWaste is an excellent resource for moving up the Organics Hierarchy and preventing and reducing discarded food. Although improving composting rates is important, it should be stressed again that composting is not a silver bullet for our issues related to food waste. Governments, businesses, and community members should all be striving to design out and eliminate waste, rather than management, to move us towards a sustainable, circular and, regenerative future.

Learn more about our world with our useful resources.